- Home

- Carole Radziwill

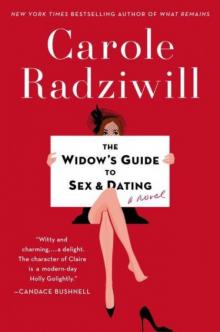

The Widow's Guide to Sex and Dating

The Widow's Guide to Sex and Dating Read online

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Acknowledgments

Thank you … to the supremely talented team of Michael Carlisle, Lauren Smythe, and Richard Pine for finding a home for this book and for their unwavering belief in it. Barbara Jones, my editor at Holt, for shepherding Widow’s Guide through the publishing processes with passion, wisdom, and good grace. Thank you to my publisher, Stephen Rubin, for whom I have great admiration. Thank you to Joanna Levine, Richard Pracher, Maggie Richards, Pat Eisemann, Gillian Blake, and the entire team at Holt, the most dynamic and clever publishing house an author could hope for. The support and sound advice of Alexis Hurley, Lyndsey Blessing, Kassie Evashevski, and Jason Richman continue to be invaluable. Special gratitude to Caitlin Alexander, whose editorial help came at the perfect time. To all the boys I didn’t love, and some I did. And to my friends who make me laugh every day I am truly grateful. Lastly, lifelong thanks to Teresa DiFalco, my confidante and co-conspirator, whose storytelling instincts, friendship, and faith kept it all moving forward. You have all been a great gift.

“Love is like a brick. You can build a house or you can sink a dead body.”

—LADY GAGA

Contents

Title Page

Copyright Notice

Acknowledgments

Epigraph

1. A Man Falls Dead

2. The Widow Gets Laid

3. Love Is a Drag

4. The Widow Finds Meaning

Also by Carole Radziwill

About the Author

Copyright

Charles Byrne, Sexologist and Writer, Dies at 54

by MARK IOCOLANO, The New York Times

Charles Byrne, renowned sexologist and author of the National Book Award–winning Thinker’s Hope, as well as several pivotal studies on sexual norms and morality, died Monday from a head injury incurred at Madison Avenue near 61st Street, according to a statement issued by his longtime publisher, Knopf.

Charles Fisher Byrne grew up in Bristol, Connecticut, the only son of socialite Grace Thornton and the late Honorable Franz Byrne, chief justice of the Connecticut Supreme Court.

Charles Byrne attended Princeton for both his graduate and undergraduate studies, and held several honorary degrees. He published his first academic paper on sexual paraphilia, called “Erotic Variations on a Theme,” his junior year. It contained the seeds of what was to become his most widely known theory, The Opposite of Sex, and launched the career of what is considered one of the preeminent voices in the field of contemporary sexology.

At 22, just out of college, Charlie, as he was known to his friends, was selected by Robert Rimmer to apprentice at the experimental sexuality retreat known as the Sandstone Institute, in Malibu. He remained close to Rimmer until his death and credits Rimmer’s teachings on polyamory with influencing most of his own work and life. Mr. Byrne took Robert Rimmer’s theories one step further and promoted promiscuity as an ideal state for fostering a stable, family-oriented culture. “Love and sex,” he wrote, “make poor roommates. You may find one or the other in a companion, but never both.” He believed that sexuality is the purest form of artistic expression, a theme that later proliferated in his first book, Thinker’s Hope.

Byrne’s career skyrocketed with the publication of Thinker’s Hope. It won the National Book Award and sold over five million copies worldwide. It made Charles Byrne a household name. He followed it up the next year with The Half-Life of Sex, a commercial, if not critical, success.

In 1985, after a disappointing reception for The Half-Life of Sex, Mr. Byrne wrote a series of critical essays on what he saw as the existential crisis of the penis, titled, appropriately, “The State of Erection.” His theories of Love and Sex were, once again, a central theme.

Mr. Byrne went on to publish many books in the 1980s and ’90s, including Sperm and Whiskey; Sex, Sea Songs and Sartre; and Driving with Her Head in Your Lap. He did not publish a book, however, after his collection of essays, The State of Erection, in 1999, choosing instead to focus on the lecture circuit and talk shows.

He counted among his friends a colorful variety of artists and intellectuals, from the controversial French lettriste Isadore Isou to the American comedian Paul Reubens.

Mr. Byrne is survived by his mother, Grace, and his wife, Claire Byrne.

PART I

A Man Falls Dead

1

The upshot of the story is this: A man falls dead, the widow gets laid, love is a drag, the end. In the gaps, a woman finds meaning. The man fell dead on a Monday in New York; it was sunny, there was a breeze. Birds chirped in the suburbs, trains were on time, the postmen made their rounds. It was a mild day with a calm blue sky. Thoughts in offices around the city meandered from sex to lunch plans to the e-mail about smells in the break room. The day was ripe for calamity. It was the kind of day when the brakes fail on the tour bus, the leading man falls for a woman his own age, and the elderly pair in 4B shuffle out in handcuffs with the police. It was the kind of day when no one expects anything to happen, so it does. Blue skies can be misleading.

Claire Byrne was in Texas to see a man named Veejay Singh, a doctor, but not the medical kind. He taught sociology at the University of Texas at Austin, and he’d written a book titled Why Breasts Don’t Matter. Dr. Singh was popular on campus, both for his friendly manner and for his notoriously easy grades. He was a minor celebrity, too, appearing on the Today show now and again to explain his evolutionary theories about mating. Claire was there to interview him. She was writing a profile piece for Misconstrued, the magazine “for women, like you, who defy definition!” She parked her rented car in the visitors’ section by the admin building and began her stroll toward Singh’s office at approximately ten after nine, weaving through oak trees and sun-dappled shade, her espadrilles marking lines across the dewy green quad. Claire’s husband, Charlie, was at home in New York.

Well, he wasn’t technically home.

RULE #1: Don’t screw around on a Monday.

Claire had left the previous day, so Charlie spent the afternoon and night across town with the new publicist at Knopf. They’d spent their time in the girl’s cramped studio apartment humping and screwing like dogs, but now he, too, traversed trees and dapples, crossing Central Park toward Madison to meet with his agent, Richard Ashe. Charlie had a book overdue by two years and Richard was anxious. He had a dwindling number of profitable writers and a heavily mortgaged co-op. Charlie didn’t think much of deadlines.

Charles Byrne was the world’s most famous sexologist—more mainstream than Kinsey or Masters ever were. As much sexual object as academic, he wrote on a subject that everyone likes to read about, and he looked like someone you could easily imagine in the act. At fifty-four, in fact, he bore a passing resemblance to Warren Beatty—in Bugsy, not Reds—and possessed a rough-edged but overpowering charm. He was crafty with words, engaging on many different levels, so that his appeal spread wide. When he wrote about the penis, he managed to be both educational and downbeat, couching bawdy locker-room humor in intellectual wit. When he wrote about vaginas, he wrote with the appreciative and admiring eye of a collector. His writing made even coarse men think of symphonic productions as they bedded their irritable wives. It made sophisticated men think fondly of their wives as they bedded their steamy lovers.

Charlie was thinking fondly of his own young wife as he interrupted his wa

lk for coffee at a diner on Madison, and this is a good place to play what if. You know—what if he hadn’t stopped, or not stopped for so long, or what if he’d been distracted by some small thing that slowed his pace.

In the diner, Charlie skimmed the sports page and phoned Richard to say he’d be late. He ordered a second coffee to go (what if he hadn’t?), put four dollar bills on the counter (what if he’d fumbled and only put three?), then left to resume his walk.

While Charlie was perusing pitching stats—Wang and Hughes out of the Yankees rotation, Pettitte in—Claire was taking in cowboy-booted coeds in sundresses, thinking how she’d describe the scene back to him. (Russ Meyer directing a commercial for the Gap? No, more like a Playboy production of Oklahoma.) She’d been tempted to buy him one of those T-shirts in the airport: a buxom cowgirl riding a cactus, below the slogan EVERYTHING’S BIGGER IN TEXAS. It was the sort of thing Charlie might wear under his suit coat to the theater just for laughs.

Charlie enjoyed causing a scandal; he relished the attention. Claire, on the other hand, preferred anonymity. She was a petite woman, size 4, not tall—in heels she reached Charlie’s shoulder. She had dark hair that she wore long and loose, youthful skin, pale brown eyes, and what Charlie called complicated lips—they could be plump and sensual one day, and the next day nondescript. She was attractive, yes, but she wasn’t fooling anyone. She wasn’t a girl who lounged around uninhibitedly, slugging whiskey from the bottle. She wasn’t like the women Charlie wrote about. She didn’t know how to produce cigarettes for randy men to light; she wasn’t boozy or dramatic, her necklines didn’t plunge. She was ordered and neat, in contrast to Charlie’s flair. She was the ingenue to his rogue. Charlie was the main act. Sasha, Claire’s closest friend since college, called Charlie “Sundance,” to Claire’s Butch Cassidy. “He cheats at poker and shoots up the room,” Sasha liked to say, “while you collect the chips and tidy up.” Charlie cast a long shadow. Claire had learned early on with him that one of her better qualities was knowing where to stand in it.

* * *

CLAIRE’S ASSIGNMENT IN Texas that day was dull, but drama was waiting in the wings. By the time she reached Singh’s office with its view of the tree-lined South Mall, her husband was dead. A Giacometti—a large and very expensive piece of bronze—had dropped on top of him, in an unlucky twist of fate.

Days later, looking back, it seemed inevitable. Claire couldn’t imagine it playing out any other way. One minute Charlie was strolling down Madison working out sound bites in his head for the Nobel speech he was sure he’d eventually have to give. The next minute—poof—he was dead. One minute off to a postcoital meeting with Richard, the next instant, gone. Life changes in less time than it takes to say, “Fuck.”

He’d been preoccupied. He didn’t see the thing drop from the sky. How could he? There was no warning, no fear, no panic or pain; for Charlie, it was over quickly. Elsewhere, though, there were ripples. There were witnesses, for instance, like Mona Glisan, who were affected. Reporters converged, then multiplied like flies, mining stunned tourists for sound bites. There was a noise, “a loud crack,” was how Mona described it. The bronze had been hanging from a crane and the cable holding it snapped, and she described it like that—a crack!—followed by a hollow-sounding jingle like an enormous key dropping to the ground. It made Mona’s ears ring. She put her hands over them reflexively while she described it.

The sculpture that dropped was over six feet tall. It weighed three hundred pounds and fell from twenty stories up. It had cost Walter White—his is another story altogether, we’ll come back to it—millions of dollars and was supposed to be lowered onto his terrace. Instead, it dropped on Charlie’s head.

Mona Glisan’s account was the first of many. Steve Johnson saw it, too. He was an art major at Columbia, and he spoke about the motion of the object and the illusion of weightlessness. “The absence of nothing,” he said, “is something in itself.” No one knew what he meant, but he spoke very slowly, which gave people the impression that they should. He was too slow, however, for the sergeant taking statements, who quickly moved on, leaving the lingering crowd at Steve’s mercy. “The serene elegance and grace,” he continued, “of this exquisite piece of art, floating on air…”

Alberto Giacometti, who’d made the bronze, was dead, too. A large and brooding man, he’d been known for colossal bouts of depression. He would disappear into his studio for months at a time, whittling obsessively and shunning visitors, until he emerged with clay prototypes of the unwieldy, thin, and rutted works that made his name. Charlie’s piece was called Man Walking: a tall, skinny man formed into a walking motion with his head down, absorbed in thought the way Charlie had been until the two collided in mutual distraction. The sexologist and the statue were an unusual pairing, to say the least. Their introduction was made possible by Evelyn White, Walter’s wife. Her cursory pretentions in art, coupled with the discovery of her husband’s affair, had set the whole thing in motion. But we’ll come back to that, too.

Among the others who saw the collision was a woman from Ohio visiting New York with her church group on a theater package—one of those six-shows-in-three-days kinds of things that never include first runs. She saw Mamma Mia! and The Lion King, and was viewing the Simon Doonan window displays at Barneys when she saw Charlie die. She offered herself to Channel 6. “It was horrible,” she said in a shaky voice as she wiped away tears. Then she lowered her voice an octave and addressed the camera directly. “The Lord works in mysterious ways.”

Another witness, a man from Brooklyn, performed for reporters as if he had a scene-stealing bit in a mob film—“Dere was dis huge (he pronounced it “yooj”) fuckin’ thing. Comes outta nowheh—Bam! Poor fuckin’ guy.” The network channels didn’t air his remarks, but two days later The Howard Stern Show did; Stern’s producers had him reenact the scene between strippers in a tribute of sorts to Charlie. Howard had been a big fan.

But it was Paul Bowman, an ad exec, whose account got the most play. He seemed to capture the spirit of the incident. “It was, for lack of a more original word,” he said, “surreal.”

“What went through your mind?” asked the reporter from ABC News. “Well, I think the stillness,” Paul said. “It was abnormally quiet. I felt it, that stillness. That’s what made me look up. It was like an Ingrid Bergman, or Bergmar, film, you know, that French guy. It was like everything, just briefly, paused.”

Paul’s were the words that somehow hit the mark. They played on WFAN, they ran in the New York Times, and after the Associated Press picked up his version it spent two days on Yahoo! News—Most Viewed. His estranged wife, Amy Strauss-Bowman, a film studies professor at Rutgers and the reason Paul Bowman even knew the name Bergman/Bergmar, sneered when she read his account and its gratuitous but bungled display of cineaste. Amy knew that Paul’s greatest art form thus far was to belch out the fight song during televised football games. She also knew that, obviously, a rare Giacometti fluttering down the side of a forty-three-story building against a bright blue backdrop of sky was vintage Kenneth Anger, or maybe Fassbinder, but certainly not Bergman.

The sun, after Charlie’s death, remained out. The day ticked on unmoved, though a large bronze sculpture and a man both lay still on the sidewalk. Charlie was clearly dead, but there was concern about the bronze. Walter White had been called, and Walter White summoned lawyers. A lot of money lay on the ground tended by the unappreciative eye of the NYPD. Then, too, there was concern with liability.

Sidewalk traffic bunched. Taxi drivers honked at stopped police cars. Men in suits hurried past, unimpressed. A family from Denver stood, mouths agape; the mother put a chubby hand in front of first one child’s eyes, then the other’s. Fire trucks closed in, sirens wailed.

Charlie’s denim-clad legs, toned from years of tennis, were bent at unnatural angles; his arms were askew. He’d wound up ungainly. He would have been mortified.

Paramedics moved slowly about the body. The ambulance driver l

it a cigarette and joined the firemen a few feet away. The men stood talking for a time; now and then, one would laugh. They argued over the Yankees and the Mets, and traded jokes about another stiff they’d picked up that week. Policemen continued to take statements from the witnesses, one at a time, writing in small notebooks with blue ballpoint pens. None of it came to much.

At some point midmorning the body was covered and Charlie’s limbs were secured to a metal bed. One arm slipped from beneath his sheet and dangled, the way arms sometimes do in suspense films to reveal something—a birthmark or tattoo, some important clue that has been overlooked. But this was Charlie’s right arm—no watch, no marks—and a paramedic replaced it beneath the sheet without incident.

Gawkers stayed stubbornly put. Finally, the medical examiner’s van arrived and Charlie was removed from the scene—one hour and thirteen minutes after leaving his four-dollar tip at the diner.

Another team arrived to load the Giacometti into an evidence truck. Walter White stood nervously in his doorway, inquiring. We’re taking it to the Sixty-First Precinct, Mr. White. I can’t tell you yet how long we’ll need it. We have to file the usual reports. At that moment, Walter was unaware of who the dead man was.

Cleanup, for the most part, was brisk.

Meanwhile, in Texas, Claire sat in an uncomfortable chair across from Veejay Singh and worked to establish rapport. Dr. Singh, like Charlie, moved easily between pop culture and more serious arenas. His subject specialty was the biology of attraction—the whys and hows of picking a mate. Men like long hair and big breasts, we assume. But is that really the case and, if so, why? Dr. Singh had a theory, and he’d spent five years measuring women to prove it. He circled their hips and their waists with tailor’s tape and divided the second number by the first. He compared these ratios with estrogen levels and fertility data, and through his findings he promoted his idea that men are hardwired to seek a certain shape. More specifically, his research showed that women with a .7 hip-to-waist ratio—wide hips and small waists—are good breeders. These women have the best odds of conceiving a baby, so men intuitively seek them out to reproduce. The famous hourglass figure, in other words, is not just a fashion trend but an important step in evolution.

The Widow's Guide to Sex and Dating

The Widow's Guide to Sex and Dating